[ad_1]

“For over half a century the automobile has brought death, injury and the most inestimable sorrow and deprivation to millions of people,” he wrote in his 1965 book Unsafe at Any Speed. That initiated an urgent, accelerating era of safety in design that continues to this day and has brought huge benefits. In 1967, UK road casualties amounted to 7985. By 2016, that had fallen to a (still unacceptable) 1792 and most of today’s car makers talk of a zero-accidents ambition.

The exhibition’s Making More section covers not just the exponential early-1900s build-up in car production but also oil production and mining for materials. It begins, perhaps inevitably, with a real, live Ford Model T in black. But this one has a side of pork suspended over it in recognition of the fact that Ford’s principle of the moving production line was borrowed from an abattoir.

The 1909 Model T was Ford’s third or fourth attempt to make a profitable car, but its success was extraordinary. At times during its 18-year life, more than two million cars were manufactured in a single year, a figure that outshines most modern operations. At one stage, the car held 45.6% of the US market and the story was similar in the UK, where production began at Trafford Park, Manchester, in 1911.

The rise of car production and how the same principles came to be applied to other industrial processes – furniture and clothing manufacture and even the advent of prefabricated buildings – are lovingly discussed in the exhibition, as are the ways mass manufacture led to labour organisation and some celebrated union disputes. We also learn how fashion informed car design with new techniques, colours and textures, and how model variety (distinctly lacking with the Model T) widened and deepened the worldwide demand for cars.

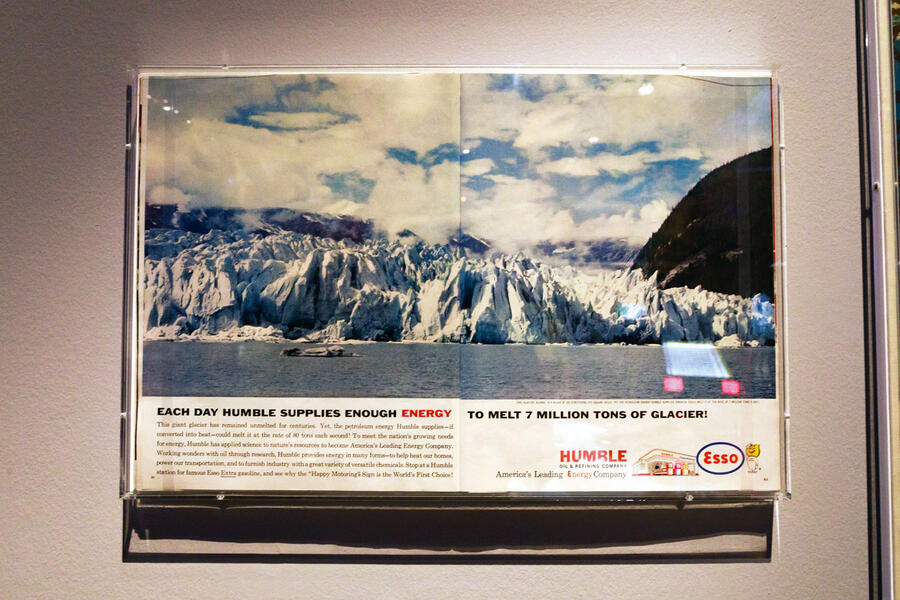

In the third, Shaping Space section, one of the biggest fascinations is an emphasis placed on the rise of oil production: there’s even a running display showing, in real time, how many barrels of crude oil remain to be exploited. It’s a big number, but falling. Another extraordinary exhibit – perhaps the most remarked upon of all – is an Esso-backed poster from 1962 cheerfully boasting that the company’s refining arm, Humble Oil, “supplies enough energy to melt seven million tons of glacier” every day. It may be the museum’s most graphic indicator that times have changed…

The exhibition flows on, revealing how cars inspired wonders of art like the Diego Rivera murals in central Detroit and wonders of architecture like Fiat’s Lingotto factory, the one seen in The Italian Job with a banked test track on its roof for cars built down below. It is a fascinating and challenging display whose sheer depth of information will surprise everyone, whether they think they know about cars or not.

[ad_2]